During my doctoral studies, I focused on measuring the rotation period of SUPERBLINK stars that were also monitored by the K2 mission. My hope was to find the rotation periods of low-mass stars in order to calibrate the gyrochronology curve which isn’t well studied for these small stars. I didn’t wind up doing that work because-let’s face it-whose dissertation has ever gone the way they expected it to? Instead, I let the data take me where it wanted me to go, and this led me to finding some interesting stars in the Galactic Halo.

The Galactic Halo

When a spiral galaxy forms, it begins as a massive cloud of gas that gradually collapses into a rotating disc with spiral arms full of stars. However, some stars form before the disc takes shape while the galaxy is still a vast, irregular cloud. As the rest of the galaxy flattens into a disc, these early stars remain in place, their orbits forming a spherical shell around the galaxy. This ancient, star-filled region is called the Galactic Halo.

We expect these halo stars to be slow rotators due to their old ages. We expect them to have high velocities due to the mechanics of their orbits. And finally, we expect them to have a low amount of metals in their composition because they were formed at a time before the gas of the galaxy contained metals which are produced by supernovae. Astronomers can use any of these features to identify halo stars. So what does it mean when a star is in the halo, but it doesn’t obey all these rules?

Identification of Unusual Stars

The dataset I used for my dissertation contains approximately 58,000 stars, and I found approximately 1,100 fast rotators by analyzing their light curves. I used python and math to do all this; I’d probably still be in grad school if I had to do this all by hand.

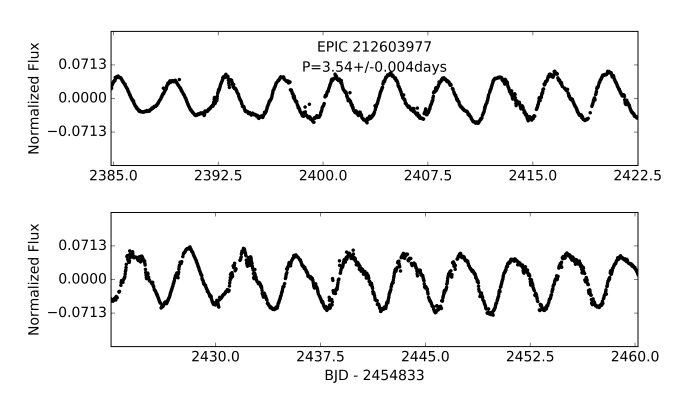

Astronomers use light curves like the one shown above to determine rotation periods of stars. A light curve is simply a measure of a star’s brightness level over time. Stars have spots on their surfaces which modulate the brightness level as the star rotates. Therefore, we can use the modulation of the light curve to measure a star’s rotation period.

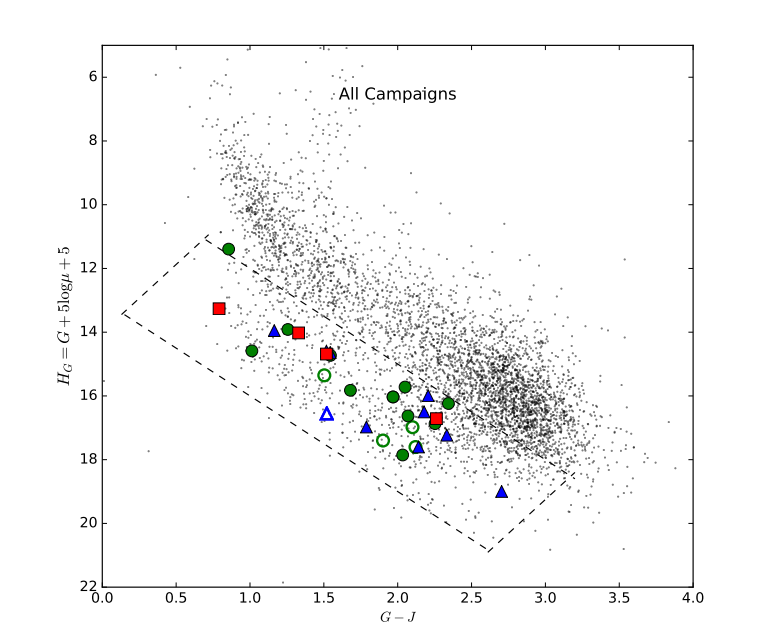

After I found the 1,100 fast rotators, the next step was to confirm they were young by looking at their other features. One way to do this is by using a Reduced Proper Motion (RPM) diagram like the one shown here.

This figure plots the RPM diagram for the stars in my data set. The x-axis is color with more red being towards the right. Redder stars are smaller and less massive. The y-axis is the RPM. While RPM behaves like a magnitude (brightness of a star), it is actually a way to estimate how fast a star is moving through space. Halo stars move faster and appear lower on the diagram. The black dots are individual stars. The dashed-line box indicates where halo stars fall on this type of plot. The colorful symbols are the unusual stars I found in my dataset.

We knew these stars were unusual because they fall in the region where halo stars would, but their light curves look like any other young star. This figure shows the light curves for 12 of the 32 unusual halo stars.

Note: this image (like this others in this post) is a screen shot from my dissertation. The hard drive with all the original files is packed in storage. Sorry the pictures are fuzzy!

So What Are They?

The short answer is: I don’t know.

And because I went into industry instead of academia I never got to study these stars in more detail. Part of my dream of becoming a high school teacher is to get back in to research as well. Currently, I don’t know how that would happen. But I do know what I would do if I could get my hands on more data.

I would collect spectral data of these stars to confirm they are metal poor, which is the best way to determine a star is a member of the halo. Spectral data also help us determine the full 3D motion of a star because the spectral lines would be red- or blue-shifted if they were moving away from or towards us, respectively. If these stars were not confirmed to be halo stars, I’d be happy that I was thorough. If they were confirmed to be halo members I would have to have a nice long think about why a 10 billion year old star is rotating like a 1 billion year old star. If anyone wants to give telescope time to an out-of-work astronomer, give me a call.

You may have noticed I only showed the light curves for 12 of the 32 unusual halo stars I found. The other 20 stars weren’t fast rotators, but they are a blog for another day. Don’t forget to subscribe below so you’re alerted when I put out new posts. I hope you’ll keep following along as I share my dissertation research. Thanks for reading!

Dicy Adams holds Bachelor’s Master’s and Doctoral degrees in Physics & Astronomy. She is an astronomer turned data scientist turned aspiring high school educator.

Leave a reply to What Spinning Stars Tell Us About Their Ages – Astro Dicy Cancel reply